scaling up bayesian nonparametric manifold learning

This is an excerpt from my master’s thesis, for which the code can be found here.

The manifold hypothesis states that naturally generated, high-dimensional data, such as images or neural activity, should be expected to lie around some low-dimensional manifold. This has been justified by the fact that natural data is generated under physical constraints which limit its intrinsic complexity. The success of machine learning methods, such as neural networks, on high-dimensional data can thus be explained by their ability to exploit this latent, low-dimensional structure.

The field of manifold learning (Bengio et al. [2014]) then is concerned with leveraging the intuition behind the manifold hypothesis to design machine learning algorithms, which can represent these geometric structures. For example, the algorithms: Isomap (Tenenbaum et al. [2000]) and Umap (McInnes et al. [2018]), apply geometric concepts to provide dimensionality reduction for data visualisation purposes.

Another area of manifold learning is density estimation. While density estimation is an established problem within statistics, being useful in downstream clustering or prediction tasks, the manifold hypothesis suggests a natural framework for estimation. This has seen particular interest from research in deep generative models (Tomczak [2022]) due the fact that such models aim to learn the distribution of our data to generate new, interesting samples. By accounting for the geometric structure of data, such models should be able to learn better data distributions for improved performance. Brown et al. [2023] presents evidence in this direction, showing that inductive biases within deep generative models, which account for the manifold hypothesis, can help improve model performance. Also, Horvat and Pfister [2023] adapts normalising flows to learn distributions supported on low-dimensional submanifolds.

In this dissertation, however, we are interested in the Bayesian nonparametric approach to density estimation. The standard way this is done is through Dirichlet process mixtures - this specifies our density by an infinite mixture model, with a Dirichlet process prior placed on the mixture’s parameters. Bayesian inference then provides an estimate of the true density. While such models have long been studied in the literature (Neal [2000]), they mainly assume that the distribution of our data is supported on \(\mathbb{R}^D\) instead of possessing some low-dimensional structure. Hence, these approaches have been shown to struggle in recovering the density of manifold-distributed data as they are unable to capture the curvature and (low) dimensionality of such structures - see Mukhopadhyay et al.[2020].

The recent paper Berenfeld et al. [2022] overcomes these limitation through introducing a new family of Dirichlet process mixtures, for which they show very good empirical performance. Theoretical guarantees are also provided to show that such mixtures are able to converge to the “true” distribution of the data, under regularity conditions. Along with the interpretability of such methods compared to black-box deep generative models, this provides a compelling solution to density estimation under the manifold hypothesis. The main drawback, however, is that inference - through MCMC sampling - is computationally expensive and fails to scale to datasets with dimension greater than two. This prevents the use of such methods beyond toy examples.

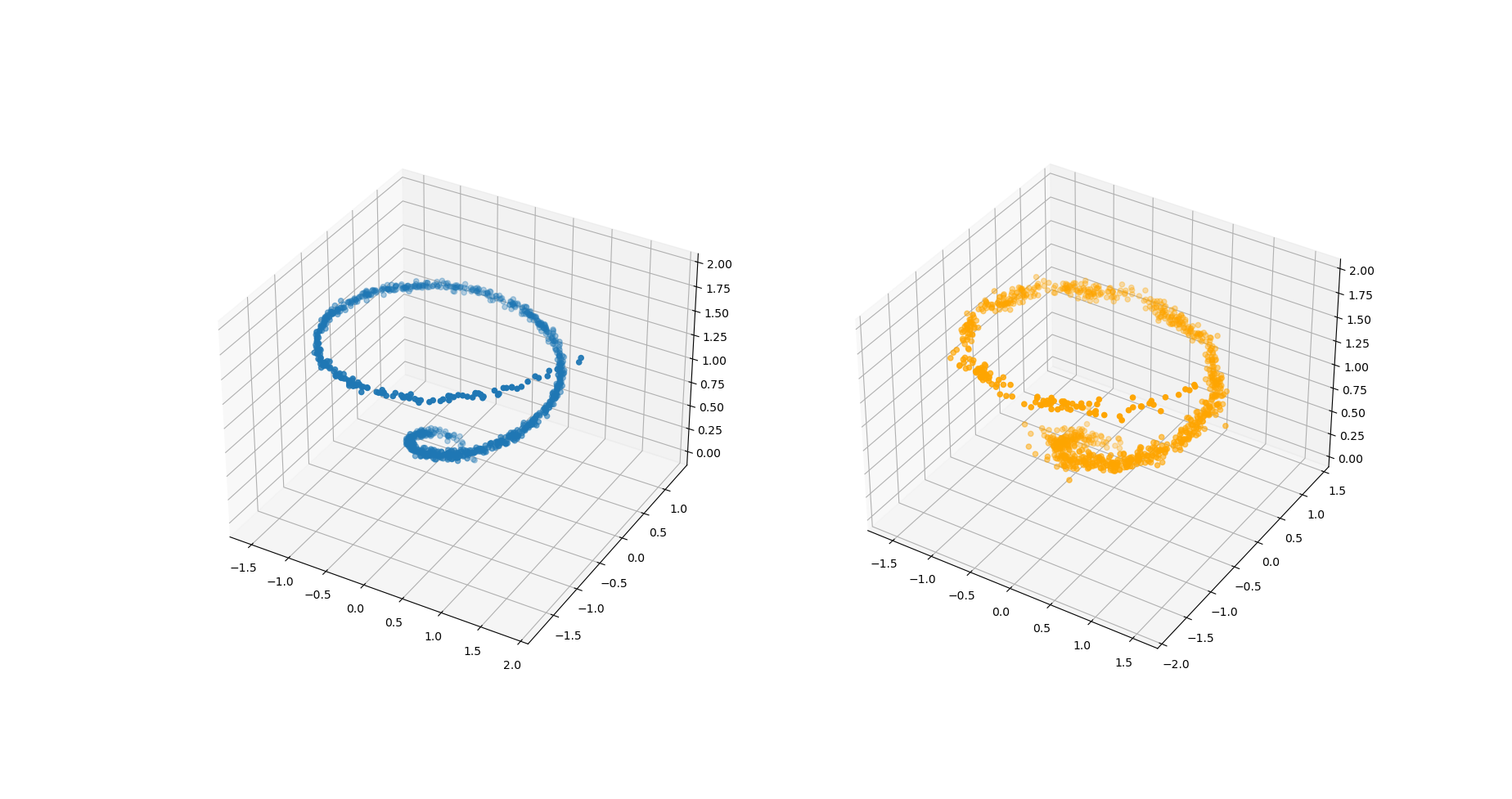

This motivates the main contributions of this dissertation. We present a variational inference algorithm to provide approximate Bayesian inference for Berenfeld et al. [2022] - see Figure 1. This allows us to scale such methods to higher-dimensional datasets, for which we empirically observe only a slight drop in accuracy. We also attempt to give theoretical guarantees for the convergence rate of an oracle variational approximation to the true parameters, in order to provide justification for the use of variational inference. We note that while we were unable to finish the proof before the dissertation deadline, our proof only requires one final technical step.

References:

Bengio, Y., Courville, A. and Vincent, P., 2013. Representation learning: A review and new perspectives. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence, 35(8), pp.1798-1828.

Berenfeld, C., Rosa, P. and Rousseau, J., 2022. Estimating a density near an unknown manifold: a Bayesian nonparametric approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.15717.

Brown, B.C., Caterini, A.L., Ross, B.L., Cresswell, J.C. and Loaiza-Ganem, G., 2022. Verifying the union of manifolds hypothesis for image data. In The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations.

Horvat, C. and Pfister, J.P., 2023. Density estimation on low-dimensional manifolds: an inflation-deflation approach. J. Mach. Learn. Res., 24, pp.61-1.

McInnes, L., Healy, J. and Melville, J., 2018. Umap: Uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.03426.

Mukhopadhyay, M., Li, D. and Dunson, D.B., 2020. Estimating densities with non-linear support by using Fisher–Gaussian kernels. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology, 82(5), pp.1249-1271.

Neal, R.M., 2000. Markov chain sampling methods for Dirichlet process mixture models. Journal of computational and graphical statistics, 9(2), pp.249-265.

Tenenbaum, J.B., Silva, V.D. and Langford, J.C., 2000. A global geometric framework for nonlinear dimensionality reduction. science, 290(5500), pp.2319-2323.

Tomczak, J.M., 2022. Deep Generative Modeling. Springer.